Disjunctive arguments can be a reverse multiple-stage fallacy

Assume we want to know the probability that two events co-occur (i.e. of their conjunction). If the two events are independent, the probability of the co-occurrence is the product of the probabilities of the individual events, P(A and B) = P(A) * P(B).

In order to estimate the probability of some event, one method would be to decompose that event into independent sub-events and use this method to estimate the probability. For example, if the target event E = A and B and C, then we can estimate P(E) as P(A and B and C) = P(A) * P(B) * P(C).

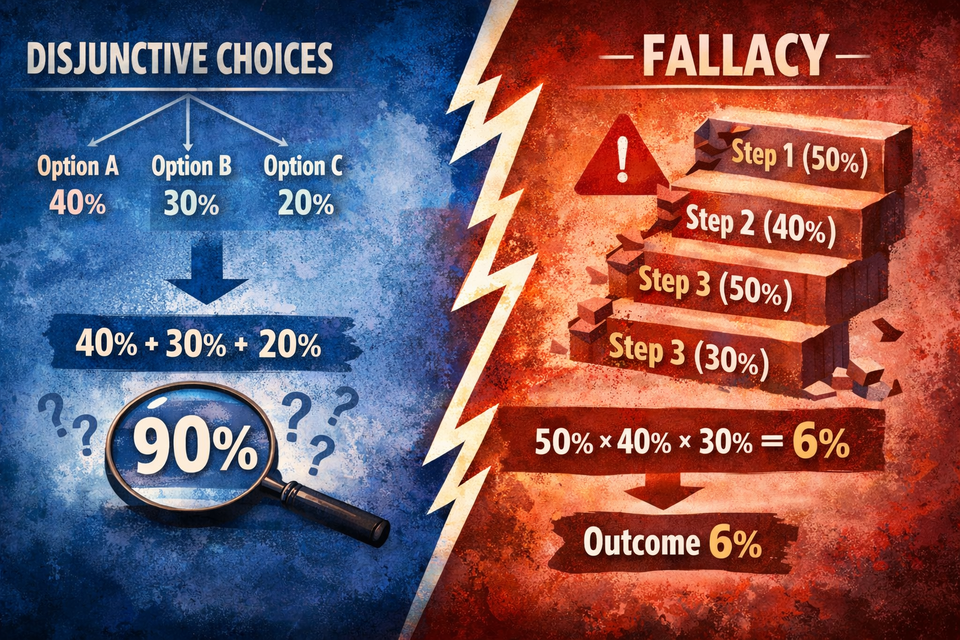

Suppose we want to make an event seem unlikely. If we use the above method but slightly under-estimated the sub-event probabilities and use a large number of sub-events, then the resulting final probability will inevitably be very small. Because people tend to find moderate-range probabilities reasonable, this would be a superficially compelling argument even if it results in a massive under-estimation of the final probability. This has been called the multiple-stage fallacy.

Assume we want to know the probability that either of two events occurs (i.e. of their disjunction). If the two events are mutually exclusive, the probability of the disjunction is the sum of the probabilities of the individual events, P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B).

In order to estimate the probability of some event, one method would be to decompose that event into mutually exclusive sub-events and use this method to estimate the probability. For example, if the target event E = A or B or C, then we would estimate P(E) as P(A or B or C) = P(A) + P(B) + P(C).

Suppose we want to make an event seem likely. If we use the above method but slightly over-estimated the sub-event probabilities and use a large number of sub-events, then the resulting final probability will inevitably be very large. Because people tend to find moderate-range probabilities reasonable, this would be a superficially compelling argument even if it results in a massive over-estimation of the final probability. I propose this is a kind of reverse multiple-stage fallacy. In practice, I rarely see people actually make explicit estimations by this method, which makes sense since usually the disjunction could involve so many events as to be impractical. Instead, in the disjunctive case, a person might just say something like "the case for X is disjunctive" and the over-estimation is implicit.

Of course, not all disjunctive arguments are necessarily subject to this critique. Over-estimation of the components (either explicitly or implicitly) is required.